Dr. Dermot Hayes, agricultural economist at Iowa State University, shared his outlook for US pork exports at the Four Star Veterinary Service Pork Industry Conference held in Fort Wayne, Indiana in mid-September.

“Southeast Asia is switching away from producing backyard pigs that scavenge or eat household and restaurant waste to one based on commercial feeding,” said Dr. Hayes. “What we are learning is that the old system isn’t viable any more in the era of African Swine Fever (ASF). This means that in a lot of the world countries will need to decide whether to import pork or to import feedgrains with which to produce pork domestically. The latter is far more expensive and will lead to malnourishment among the poor.”

Why focus on exports?

Going back to the fall of 2020, China came in unexpectedly and bought almost 7% of the US corn crop and that drove up domestic corn prices, he said. But it didn’t just drive up the price of corn for export, it also drove up the price of corn that stayed in the US for ethanol and for livestock feed.

“In a commodity market, it’s your last customer that sets the price,” he said. “In the pork business, because we’re a big exporter, it’s the export market that typically sets the price. Also, Americans are amazingly predictable in terms of how much pork we can eat at a set price, but the international markets are more volatile. So, if you’re looking for shocks in the market, you look internationally.”

Dr. Hayes said a lesson learned, especially in Southeast Asia, is that the US can export products there that are not in demand in the US. In so doing, this will reduce the breakeven cost of loins, tenderloins and bellies for the US consumer because the US can take the feet, head and intestines and sell them into a market where they’re worth $1 per pound or more. This increases the overall value of the carcass which reduces the breakeven price. While the US consumer is well-provided with pork, Dr. Hayes sees a growth opportunity for US pork exports.

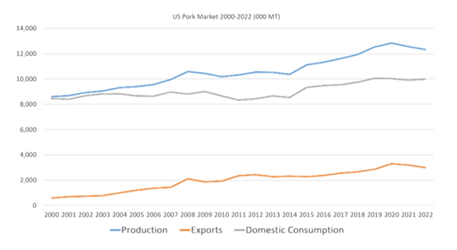

US pork consumption has increased in line with population growth, but there’s been significant growth in US exports since 2000.

“Exports were almost zero in 2000, and now we’re exporting between 25% to 30% of our pork,” he said. “The question remains if that growth can continue and are there good fundamentals behind it?’”

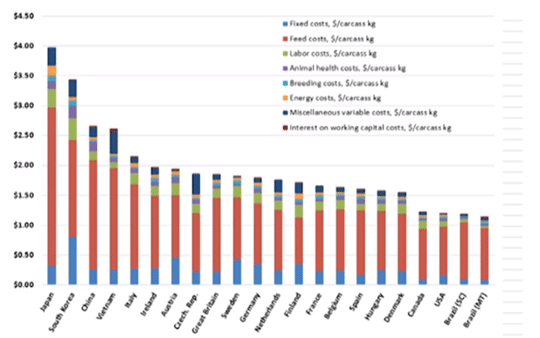

In the graph above, the height of the bar represents the cost of producing a pound of pork. The US, Canada and Santa Catarina, Brazil are the low-cost producers. Mato Grosso, Brazil has foot-and-mouth disease, so they are not a player in the pork export market. Dr. Hayes said he’s been to Santa Catarina, and they don’t have a lot of room for pork expansion.

“In the graph, the red bar represents the feed cost, and China is spending more than $2 per pound for feed. The reason for that is they are at import parity, that is at the margin. Their soybean meal and corn prices are set by the import price because they are consistent importers.”

It can be very costly to move commodities across the ocean to other countries and then on a farm in-country to be fed to livestock. It can double the cost of production or more when you have to feed at import parity, he explained.

The expense of shipping pork

“If you’re moving frozen pork, it costs 15 cents a pound to go from Iowa right into Hanoi, Beijing, Shanghai or Tokyo. We’re not doubling the price of pork; we’re adding 15 cents plus margin to the cost of the product,” he explained. “It’s more efficient, from a transportation and logistics perspective to move the raw material rather than the finished product.”

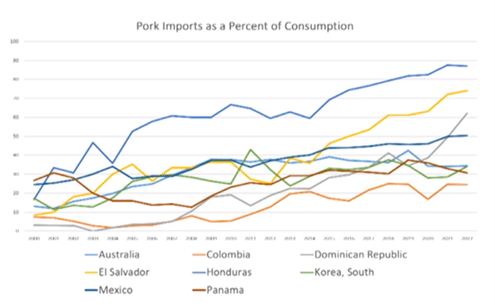

The chart above shows the percent of imported pork consumed in a country. Dr. Hayes said it’s a measure of the opposite of self-sufficiency; it represents import sufficiency. For example, Honduras imports about 90% of the pork consumed.

“The US does have free trade agreements with the countries listed, and that’s the point. What had been happening in the past is these countries were restricting pork imports and allowing in feed grain imports. So, they were tilting the balance away from importing the final product back towards the raw material. If economics are allowed to work out, instead of buying soybean meal and corn from the US, those countries will buy pork from the US.”

He said the self-sufficiency argument doesn’t matter if you’re relying on a country for your feed or your final product. There’s no argument against trade because you’re already dependent on imported feed.

“Generally, over about a 10-year period, they go from buying no imported product to about 20% or 30% or 40% in the case of Japan and South Korea,” he said. “To think about why a country like El Salvador or Honduras would buy imported product, would you invest expensive capital in poor production facilities in countries that are so economically uncertain? You would need an enormous risk premium, and investors are not willing to do that. It’s just simply better to buy the imported product.”

The whole sector is shocked about the fact that they still have 20% or 30% of their domestic production that was relying on household and restaurant waste, and that’s not viable anymore, he explained. Thus, these trends will continue, not because we have new agreements, but due to the shock to the system because of ASF.

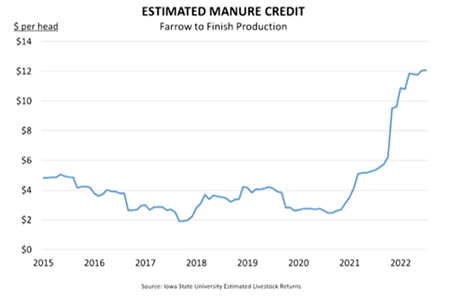

Cost to dispose of manure

“In Belgium, it takes at least $10/pig to get rid of the manure. In Holland, the government just further restricted how much manure can be applied; they’re going to have to dry it and move it out of the country,” he said. “In Upper Saxony, Germany, the value of land is huge because they need to control the land upon which to apply manure. It’s very expensive in Europe to dispose of manure.”

Dr. Hayes said he and his wife farm in Iowa, and they put in two manure easements.

“We are so lucky the last couple of years to have that inexpensive manure,” he said. “The slide (above) shows how much value there is in manure in the US – the value is $12 per pig right now, which gives us a $12/pig advantage compared to European countries who have a $10/pig disadvantage.”

Pork exports in 2022

Shifting from the long-term where Dr. Hayes believes the US has a lot of potential for growth, to the near term where he sees a lot of industry challenges.

Shifting from the long-term where Dr. Hayes believes the US has a lot of potential for growth, to the near term where he sees a lot of industry challenges.

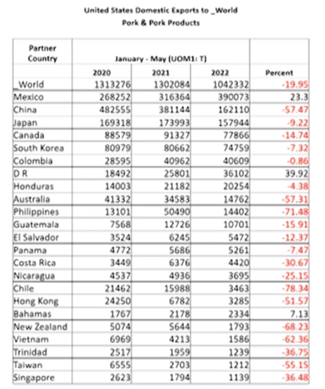

“The punch line is that this year has been a terrible year for US exports,” he said “Notice all the red entries here. We were up in Mexico 23%, but we’re down 20% overall. In South and Central America, we’re about holding even, but we’re really losing out in places like Southeast Asia – the Philippines, Vietnam, Singapore and Australia.”

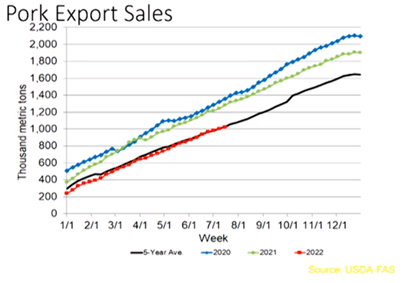

To put the 2022 data into perspective requires a look at 2020 and 2021 data of weekly export sales accumulated for over the calendar year.

“What has happened is we went from two extremely good years to a normal year, but we’re down 20%, because we had been up 20% for two years,” he explained. “Let me go through what happened in 2020. China had African swine fever and in 2018 and 2019, they culled a lot of pigs. In 2020, China really needed pork, so they came to the US and some months were we shipping 12% of everything we produced to China. It wasn’t all deboned; a lot of it was what’s called six-piece carcasses where we cut the carcass into six parts – we keep the middle parts here – then ship the end pieces over to China where they would do the deboning, partly because we were short on labor at the time. So, it was a phenomenal opportunity for us.”

The US has always faced a 25% duty in China that nobody else pays which is left over from the trade war, he said.

The US has always faced a 25% duty in China that nobody else pays which is left over from the trade war, he said.

“A little later, China could be a little more price conscious; they weren’t in such panic to buy pork, and they went to Europe to buy pork to replace the more expensive pork they were buying from us,” he said. “European pork exports, especially Germany and Spain, really shot through the roof, but then we (the US) backfilled into the markets where they would have been. Our exports to places like Southeast Asia, Vietnam, the Philippines were really good. Since then, China has rebuilt its sow herd, and European pork is swamping the market to our detriment in the US.”

US pig market

On the domestic front, during the first six months of 2022, the US was not killing as many pigs as we had expected. There was a small reduction in the number of sows, but that should have been offset by an increase in sow productivity, he said. However, there were weeks in 2022 that slaughter was down 5% over 2021.

“Anecdotally, I’ve been told that it has to do with a very virulent version of PRRS,” he said. “We weren’t killing as many pigs as expected and if you don’t have the pork to export, you’re going to be down overall.”

Also, in 2021 and 2022, the domestic consumer has been willing to pay quite a bit more for pork, creating the strongest year for domestic demand that Dr. Hayes has ever seen. He speculated that it could have to do with the pandemic assistance checks (Economic Impact Payments) going out; people weren’t eating out; they built up their savings. Coming into 2022, the savings rate was the highest on record, he noted.

“There was just more money in the economy. I had always assumed that the demand for pork had maxed out, but it turns out that if you give people a lot more money, pork consumption does benefit,” he said. “So, the punchline on this year’s exports is that we didn’t produce as much pork as expected; we demanded more pork and were willing to pay a higher price in the domestic market; European countries had a surplus to export because China had rebuilt their herd; we pulled out of our price sensitive markets. It doesn’t mean that it’s all bad – price sensitive customers will buy our pork when we have a surplus at a cheap price. But if we have a scarcity of product in the market, they’ll back off and give the US consumer access to the pork.”

Dr. Hayes bottom line

The pork industry with grow and exports will continue for good fundamental reasons, he said.

“That’s good from a financial perspective but it exposes us to us getting African swine fever or Foot-and-Mouth Disease because we would really have to drop the value of our hogs to get consumers to buy 30% more pork,” he said. “If we get African swine fever, we will lose most of our export markets, and it’s something that every producer should be aware of.”

The US government has put in place a two programs called Livestock Gross Margin and Livestock Revenue Protection that work similarly to crop insurance.

“These are like out-of-the-money put options – you can buy them for 50% of fair value through your crop insurance agent,” he said. “I think they are hoping that farmers will use these as out-of-the-money options to protect against catastrophic risk. Because they’re subsidized, there’s been a lot of interest in them. I advise you to talk to your private insurance agent because if we get African swine fever or Foot-and-Mouth Disease, we are in a world of hurt.